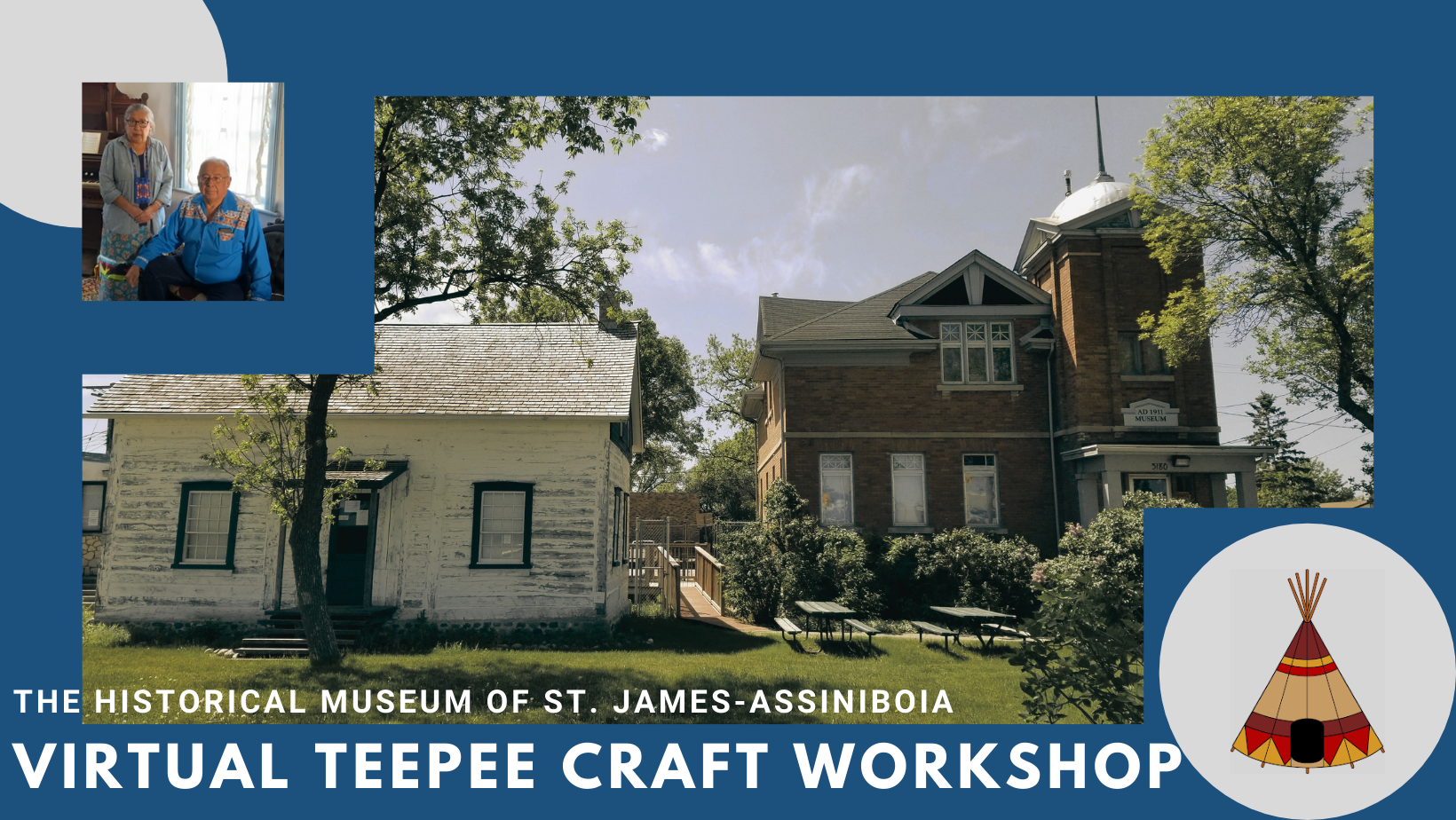

Virtual Teepee Craft Workshop

Follow along with your Teepee Craft kit to make your very own Teepee Craft:

Follow along with your Teepee Craft kit to make your very own Teepee Craft:

Schedule of Events:

(time indicates start time in video above)

0:00 Welcome from Executive Director/Curator Bonita Hunter-Eastwood

2:10 Land Acknowledgement and Blessing by Museum Elders Barbara and Clarence Nepinak

8:40 Marty Morantz, Member of Parliament for Charleswood-St. James-Assiniboia-Headingley

12:35 Honourable Scott Fielding, Member of the Legislative Assembly for Kirkfield Park

14:40 Councillor Kevin Klein, St. Charles-Tuxedo-Westwood

16:40 Councillor Scott Gillingham, St. James

19:45 Erin Okrainec, Fiddler

42:10 Indigenous Drumming Workshop presented by Elders Barbara and Clarence Nepinak

48:30 Summer Bear Troupe, Indigenous Dancers and Singers

1:03:20 Celebrating 100 Years of St. James inside the 1911 Municipal Hall

1:14:00 Jason Eastwood, Classical Guitarist and Composer

1:36:50 Tour of the 1890s Interpretive Centre

1:51:05 Historical Theatre inside the 1856 Red River Frame House

2:01:50 Red River Folk Ensemble, Franco-Manitoban Jiggers

Heritage Day Photography by Zen.

Features Indigenous teachings presented by Museum Elders Clarence and Barbara Nepinak who have delivered educational programs to Indigenous based schools including workshops, performances, and teachings throughout the world.

This free programming is made possible through Safe at Home Manitoba.

Extracted from B.G. Hunter-Eastwood, “Report on the William Brown Heritage House,” Prepared for the Historical Museum of St. James-Assiniboia, Winnipeg, 1988, p. 245-247.

Economic transaction in the Red River Settlement and, later, in Headingley had to do with land, with goods for household and personal use, with farming implements and livestock, and with labour. Goods could be purchased with cash or, by exchange, with other goods or labour. In the early stages of development of this local economy, it is quite likely that cash was reasonably scarce and that barter took up a larger proportion of economic transactions in comparison with later years. For example, Taylor’s account ledgers for 1864-1867 show that William Brown Sr. and his family paid for goods with “a day’s reaping”, with meat and with eggs, and with cash. The family also bought most items on credit: most items were purchased with a small amount down and partial payments 1-5 months later.

The relative scale of land, goods, labour and capital should also be noted. William Brown Sr. contracted with the Hudson’s Bay Company for L17 per year. His Headingly land purchases (Lot #1367 and 1368 in 1856 and Lot #1366 in 1859) cost 7 shillings and 6 pence per acre and carried a total cost of more than L108 for the 290 (plus) acres. The cost of the land represented roughly 6 years wages at William Brown’s rate of pay while in the employ of the Company.

John Taylor priced ‘one days reaping’ at 1 shilling and 6 pence in 1864 and, in comparative terms, this meant that William Brown would have had to work for six days to pay for a girl’s hat or a half-pound of tea. By the same yardstick, a good quality coat was worth roughly 11 days labour in 1864. Brown’s total purchases from John Taylor in 1864 would represent approximately three month’s labour at the rate used here. John Taylor’s Headingley Journals also record the relative scale of economic values and these can be summarized as follows. In the late 1870’s, a man could be hired for a month at $8.00-12.00. An ox would be worth roughly 4 months wages at this rate, while a moderately good horse would be worth more than a year’s wages. Viewed in these terms, William Brown Sr.’s possessions in 1849 (including 6 cows, 10 calves, 1 stallion, 1 mare, 6 oxen, and 4 pigs) represented a substantial holding. In later years, William Sr. (or William Brown Jr.) is listed in the Tax Assessment Roll for Assiniboia as having 40 acres under cultivation and livestock amounting to 11 cows, 4 horses, 7 oxen and 8 hogs. While the wages paid to farm labour had risen by this time (1881) to $10.00-12.00 per month, the livestock alone represented roughly $1800.00 or 15 years worth of work at labourer’s wages. Two account ledgers from John Taylor’s Headingley store have been preserved for the historical record.1 These provide some details of transaction specific to William Brown Sr. and his family for the years 1864-1867 and 1873-1876 respectively.

1 Provincial Archives of Manitoba. MG14, B61, 1857-1869, 1872-1878.

Extracted from B.G. Hunter-Eastwood, “Report on the William Brown Heritage House,” Prepared for the Historical Museum of St. James-Assiniboia, Winnipeg, 1988, p. 56-60.

It is difficult to provide more than glimpses, hints perhaps, of William Brown’s early life in the NorthWest and later on in the Red River Settlement. The intervening distance of more than one hundred and fifty years reduces the overall sharpness of focus and makes it difficult to relate the historical record to aspects of an individual’s life. Quite often it is necessary to generalize from what we know about the ‘average person’ to what we think was likely in the specific instance of William Brown. The following discussion will attempt to draw a sketch of life in the Red River Settlement, drawing on a variety of sources. The hardships of the early settlers in Red River have been well-documented elsewhere and it is simply necessary here to establish some common themes which may prove useful in later interpretation.

On his retirement to Red River, William Brown would have been part of a small settlement at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. William’s first contract with the Hudson’s Bay Company was dated only 9 years after the North-West Company and the HBC terminated their rivalry in the NorthWest in 1821. The construction of Lower Fort Garry began one year after William first took ship at Stromness, and Upper Fort Garry was started in 1835, the same year in which the HBC Accounts ledger tells us that he ‘retired to Red River.’ The Upper Fort had begun to flourish by the time William retired from Company service in 1841. As one retrospective sketch has stated:

This was the centre of business, government, education, and public affairs for more than thirty years, and was the nucleus of the city of Winnipeg. The fort was sold in 1882 and the front gate is all that remains of this historic group of buildings.1

The non-native population tended to be heavily Protestant, reflecting the preference of the HBC for Scots and Orkneymen as employees. A heavily pastoral account from the early 1850’s describes the Settlement as follows:

The neat little white frame and log cottages with their well-cultivated garden spots and field enclosures, have an air of charming and quite repose, while in the distance, the grazing troops of cattle and horses dot the plains with gentle animation. Here and there a windmill, or a pointed church spire, lends an additional and suggestive beauty to the landscape. Here they live in peaceful simplicity, and in all the rural quiet of their ancestral village hamlets among the highlands of Scotland.2

The population of the entire Settlement, which one observer estimated at “ten to twelve thousand” by 1868, also contained a substantial proportion of “mixed breeds of French and Indian lineage, descendants of the courriers-du-bois, who, after the expiration of their service in the companies, have settled here and married Indian wives.”3

William Brown is not likely to have had the kind of pastoral existence attributed by the un-named author of the early 1850’s. Further, William had by 1850 married a woman of Indigenous descent, and there is strong evidence in the historical record that other men of Scottish or Orcadian origin commonly married Indigenous women. They did not hold themselves aloof in the manner in which Marcy elsewhere describes as those “who have maintained their nationality intact, without any commingling with the aboriginal race.”4

Early settlers had first to prepare land to which they had access, either as owners or as tenants, and the difficulties of doing so were several. The land had first to be cleared of trees and brush; then it had to be broken with plows drawn by oxen or horses. Oats, rye, barley, and wheat could then by sown by hand. As a consequence, the area which each farmer cultivated tended to be small, and the chances of economic success poor. In the first real estate census in 1832, for example, a Mr. Kauffman had 7 acres under cultivation. In the Census of 1849, the population of Red River was 5,391. There were “754 houses…[and] Cultivated land amounted to 6,329 acres.”5 A reasonable estimate would therefore place the average size of cultivated land worked by a single farmer at something less than 10 acres. This argument is supported by the fact that thirty-odd years later, in 1881, Magnus Brown had one the largest areas under cultivation in Headingly: 50 acres. This is likely to have been substantially larger than the area cultivated by his father in earlier years.

In terms of the latter point, crop failures were common, despite the fertile soil of the region. Locusts, drought, early frosts, and late flooding were common. For example, during the years 1813-1856, there were 21 full or partial crop failures in the Red River Settlement.6 Inasmuch as the chances of failure were roughly 50/50, many farmers supplemented their farming activities with the buffalo hunt, trapping, or freighting goods. In the two latter activities, the economic influence of the Hudson’s Bay Company would have been considerable, since it dominated the trade in goods of the region, provided some of the necessities of life such as salt and clothing, and was a source of currency for value received. It was also the owner of the milling equipment which farmers required to produce flour, crushed grain and “shorts.”

There is some evidence that William Brown fit this general pattern. He was a farmer in St. John’s parish; he possessed carts which could have been used to carry goods for the Hudson’s Bay Company or for other settlers; and he may well have continued to employ some of his fur-trade skills in trapping during the first winters of his retirement. He had an account for ‘Sundries’ with the Hudson’s Bay Company, with a balance of L 10/ 2/6 in June of 1858.7 It is also possible that William Brown engaged in the production or procurement of pemmican for the Company or in market gardening for the Company store or its personnel.8

1 E.K. Paul, “H.B.C. and Manitoba”, The Beaver, Volume IV, October, 1923, p. 5.

2 No author, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, June 1851, p. 174.

3 R.B. Marcy, Op. Cit., p. 287.

4 Ibid.

5 W.F. Green, Red River Revelations, (Winnipeg: Red River Valley International Centennial, 1974-1976), pg. 154. The reference to Mr. Kauffman is to be found on p. 148.

6 G.H. Sprenger, “The Metis Nation: Buffalo Hunting vs. Agriculture in the Red River Settlement (Circa 1810-1870)”, Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology, Volume 3, No. 1, 1972. pp. 168-169.

7 HBCA E. 7/52 (b), Colonists Accounts with HBC, Outfit 1858, Red River Account Book, p. 2, under Dr. (Debit) Stock.

8 K.D. McLeod, editor, The Garden Site, DkLg-16: A Historical and Archaeological Study of a Nineteenth Century Metis Farmstead (Manitoba: Historic Resources Branch, Department of Cultural Affairs and Historic Resources, 1983). McLeod notes that a major aspect of the bison hunt was its dependence on the credit/debit system maintained by the HBC. Many families were indebted to the Company as a result and, as we saw earlier, William Brown did not emerge from his HBC employment untouched by this system.

“Fall brought with it the harvest and the danger of frost or an early snow. Grain was cut and stooked in the fields by hand; later it was built in large stacks ready for the threshing crews, who went from farm to farm. In a good year, the grain was cut, stacked, and threshed dry. In a poor year, the grain could be frozen, with little to be saved from the crop. Taylor records at least 10 years in the period 1878-1900 in which the crop is below normal in yield or quality. In the event that the crop could be gotten off the land in good order, the farmers’ next tasks were to plow and to burn stubble. Taylor wrote that, on several occasions, prairie fire started as a result of stubble burning and that there were considerable losses in some instances. Most often, the losses were higher in the hay fields than in the grain stacks. Finally, in the late Fall and early Winter, the grain would be transported by wagon to the Mill….

In the Fall of the year, the Browns frequently went hunting for rabbit, geese, ducks, prairie chickens, and wild turkey. Taylor recorded hunts in which he participated with Brown brothers (John, James, Magnus, and William Jr.). He wrote of several such hunts in which each hunter took home more than a dozen ducks or geese and often 15-20 rabbits.

During the Fall of the year, the farmers of Headingley also gathered the garden vegetables and most of these were stored in the root cellar for later use. Potatoes, onions, turnips and parsnips were cleaned and dried in the open air and then bagged for storage; some of the crop might have been sold, but this appears to have been relatively uncommon, if the Taylor Journals represent farming practices accurately.

Some of the livestock such as chickens, turkeys, and pigs were also killed at this time of year – the fowl plucked and dressed and then sold, while the pigs were scraped and cleaned with boiling water and then butchered. Most of the pork was salted or smoked for later use…”1

John Taylor of Headingley recorded the following in his journal during the fall months:

1 B.G. Hunter-Eastwood, “Report on the William Brown Heritage House,” Prepared for the Historical Museum of St. James-Assiniboia, Winnipeg, 1988, p. 67-68.

“In early spring, farmers were on the land with the first disappearance of the snow cover. Prior to planting, they cleaned the grain, soaked it and loaded it in wagons for transport to the fields. They cleared the land and plowed it and their main enemies were a late winter with a lasting ground cover, or water on the fields resulting from heavy rains or floods. In some years, crops were in the ground in the middle of March; in others, planting was not finished until late May or early June. The work was done with teams of horses or oxen and it was labour-intensive. Men such as William Brown, with several sons, used family labour extensively and they hired other men at time of peak load such as the harvest. Spring was also a time for cleaning up around the byres, cleaning the chicken coop and the root-cellar, and preparing the planting of vegetables. Generally, they planted the kinds of grains noted earlier plus potatoes, cauliflower, mangle, peas, turnip, squash, onion, tomatoes, fruit trees and berry bushes.

They also attended to the stock, including putting the newly-delivered mares to studs owned by themselves or by their neighbours. William Brown Jr., for example, owned a bull. His neighbours would pay a fee ($1.00) to service one of their cows. The service of a stallion was more dear, ranging in price from $5.00 to $10.00 and, as a consequence, many of these men would offer up to $500.00 for a good stallion.”1

John Taylor of Headingley recorded the following spring activities in his journals:

1 B.G. Hunter-Eastwood, “Report on the William Brown Heritage House,” Prepared for the Historical Museum of St. James-Assiniboia, Winnipeg, 1988, p. 64.

“The summer months normally involved construction work: painting, mixing and applying mortar, putting up fencing, and preparing storage for the harvest. According to John Taylor’s Journals, many of his summer days were spent digging and weeding in the garden, cutting wood, or doing statute labour on the public roads. He also spent time driving back and forth to town, and hauling goods, largely for his own use. The summer was also a time for picnics, horse-racing, sports, and exhibitions. The Orangemen’s Parade on July 12 was a big event to which many turned out. The same was also true of the annual school picnic. In the 1890’s rail cars from Winnipeg brought sightseers and church picnickers to the Headingley area, often to conduct festivities on a farmer’s land.”1

John Taylor of Headingley recorded the following in his journal during the summer months:

1 B.G. Hunter-Eastwood, “Report on the William Brown Heritage House,” Prepared for the Historical Museum of St. James-Assiniboia, Winnipeg, 1988, p. 65.

Explore art and history through a photographic art show and lecture by Barry Hillman, a professionally trained photographer and artist with works displayed in Europe, Canada, and Hawaii.

This free programming is made possible through Safe at Home Manitoba.

Featuring a former Dalhousie University professor of music who has performed across Canada.

Romantic guitar concert for Valentine’s dinner. Take a romantic tour of historical music through the classical guitar, a great dinner companion on this most romantic day of the year.

This free programming is made possible through Safe at Home Manitoba.